Touro Trained Us to Listen and Lead

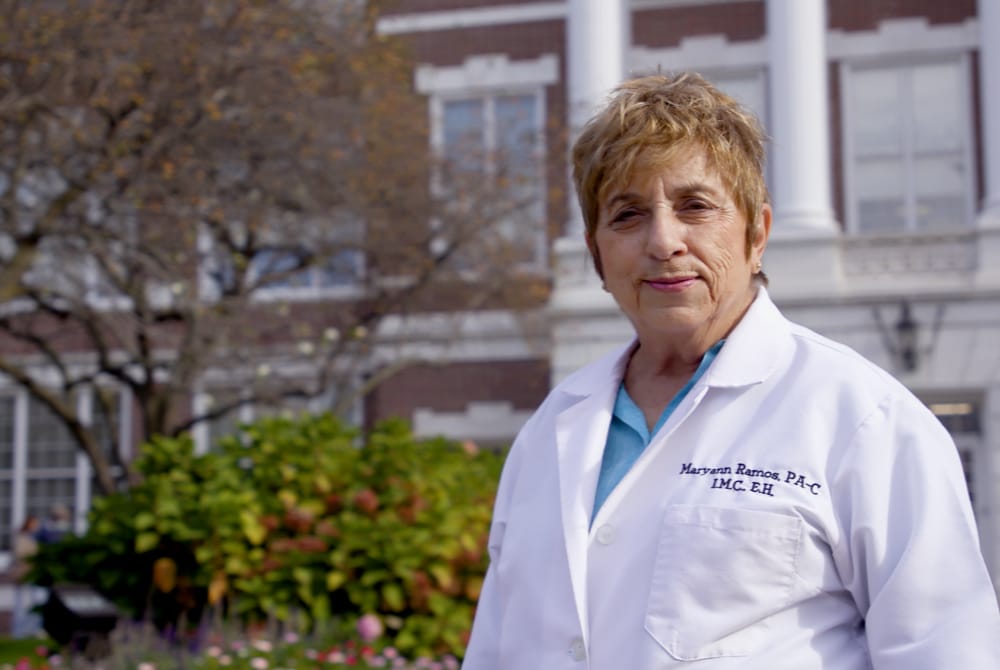

From Advocating for her Profession to Saving Lives on 9/11, PA Maryann Ramos Embodies Touro’s Values and the PA Spirit

On one of America’s darkest days, a Touro-trained PA was there to help the wounded and save the injured. 9/11 began as an ordinary day for physician assistant Maryann Ramos. A member of the Pentagon’s civilian workforce, she began seeing patients at seven-thirty on the morning of September 11. After several appointments, someone called her over to look at the television. Together, she and her coworkers watched in horror as a plane hit the Twin Towers. Then she heard a thud.

“When we walked out, I could see the smoke coming from the opposite end of the Pentagon across from us,” Ramos told the Greenwich Time paper. “It was big, black smoke that was gray on the outside. I didn’t know at first it was another plane. I thought it had been a bomb.”

While still in civilian clothing, she convinced officers to let her in to a cordoned off area and quickly went to work setting up triage services where she treated patients until she was relieved at six in the evening. Unique and terrifying as the day was, for Ramos it was a continuation of the work that began when she enrolled as a student in Touro’s first physician assistant class in 1972.

How Her Medical Career Began

Ramos always nurtured an interest in medicine but as a woman in the early seventies, her choices were limited. When she was a student in Fordham University, she made a deal with a fellow student, the man who eventually became her husband. “We talked about our professions,” said Ramos. “I would help him become a psychologist, get his PhD, and then he would help me become a physician.”

When Maryann met with the dean at Rutgers’ medical school, he told her she was too old to start medical school, and a mother. “It was 1969,” Maryann laughs. When a friend told her about Touro’s nascent PA program, Ramos saw her opportunity to enter the medical field and quickly applied.

“Touro was a wonderful place,” recalled Ramos. “They made sure that the physicians teaching us came from different subspecialties of medicine. Touro gave us a very broad education and it gave the true feeling that once we got on a floor or into a private practice, we could help with the team…we were going to be a positive asset. And I think that is still true today.”

The program was an intense one, made even more difficult by Ramos’s hour-and-a-half commute each way and her caregiving responsibilities with her husband for their two children. But she recalls the time fondly.

“It was exciting to learn medicine from active clinicians and to see how we as physician assistants could fit into the medical delivery system,” said Ramos. “The physicians that they chose to teach us were so focused on their knowledge and the transfer of that knowledge to us without hurdles. It was as if they were teaching medical students.”

After graduating, Ramos quickly found a position as the first PA in an 1100 bed VA hospital, both a testament to her abilities and the need for the brand-new addition to the medical practice. Functioning as the first member of a new profession was daunting, but Ramos dazzled. “Since I was the first PA in the hospital, I was representing the profession,” she recalled “I had to be the person that I wanted a good PA to be.”

A New Career in the Frontiers of Medicine

Ramos’ first position was in the pulmonary ward of the Brooklyn VA. There, she helped use what was a then-revolutionary way of scanning for cancerous tumors in patients’ lungs, the bronchoscopy. “This allowed us to look into the lung for cancerous tumors without cutting into the actual lungs,” she said. After a year, Ramos transferred to another VA hospital closer to her home in New Jersey.

Ramos’s abundant care and concern for her patients was clear from the start. She recalled a medical mystery that stumped the doctors in her unit. Veterans diagnosed with tuberculosis weren’t getting better despite the effective drugs used to treat the disease. The answer required Ramos to do some old-fashioned detective work and deduction. “I looked up their medications and discovered that the drugs were being broken down in their livers,” said Ramos. The veterans, she learned, were given three-day passes for the weekend since the drugs made TB untransmissible. “I looked at them and most of them used the pass after their Friday morning medicine and they’d hang out in bars to see their buddies and they’d end up drinking.”

“And even if they drank five drinks, that meant over the day, they weren't intoxicated necessarily, but their liver was busy detoxing any alcohol they had,” she explained. “So, the liver was being used elsewhere and it could not be used for the medications. I sat at least six of these young men down. And I said, here's what you need to do. I could send you to the psychiatrist. He or she could teach you how not to drink when you go and see your friends. And in three months or less, I think you would be sterile of all of the tuberculosis problems. And they did that, and they found they were getting better without the drinking.”

In gratitude the veterans bought her a watch. “It’s one of my medals,” said Ramos. “It reminds me that a good PA goes beyond just the diagnosis.”

Fighting for PAs Everywhere

While she worked in the VA, Ramos was a tireless advocate for the profession and her fellow PAs. She founded and led the New Jersey State Society for PAs. With funding from The American Academy of Physician Assistants, she lobbied legislators in the state to develop legislation codifying the rights and responsibilities of the profession.

“We were up against a barrage of advertising from nurses who initially viewed PAs skeptically,” said Ramos. “There were ads in the papers against PAs with headlines like, ‘70,000 nurses can't be wrong. The PA doesn't belong in New Jersey’.”

When she and her family moved to Connecticut, she worked with the Connecticut PA Society. “We wanted better laws for PAs in the whole state and also the ability for PAs to have prescriptive practice,” said Ramos. For her work in developing the PA profession in the state, she received a plaque from the state legislature.

“When I first started at the Brooklyn VA, they considered PAs lesser professionals,” said Ramos. “They didn't realize how well we were trained.” After her work in the VA hospital system, Ramos spent time working at Yale and teaching in the City University of New York. In 1993, she joined the Pentagon.

An Angel of the Pentagon

Ramos is still haunted by what she saw that day.

“One of our cases was a woman who was only 23,” said Ramos. “She had no blouse on her back since it had been burned off, probably by a blowback. Her skirt was intact since it wasn’t synthetic. But her legs had been burned so badly that the skin on them was hanging off. She died two days later, but I was able to get her to an ambulance so she could get seen in the hospital immediately. Those were the kind of things we saw until 7 p.m.”

Ramos was photographed treating US Army Captain Lincoln Leibner and the iconic image became the cover of the 2002 U.S. Medicine magazine.

When she retired from the Pentagon in 2008, Ramos received the Civilian Superior Performance medal. She also received an angel figure in a red, white, and blue blouse by a patient who described her as “the angel of the Pentagon.”

The Work of a PA is Never Done

Despite retiring, Ramos is still active. She is part of the Connecticut branch of the Medical Reserve Corps, a federal organization composed of 200,000 volunteers who respond to public health emergencies and participate in health-related activities.

She was called up to help during Hurricane Sandy and the recent Covid-19 pandemic. On the legislative front, Ramos is working to introduce proper PA legislation to Puerto Rico to help patients on the island.

“What I'm most proud of in my career is that I was able to make a difference with certain patients that didn't ever have anyone listen to them carefully,” concluded Ramos. “And so, I was able to get that [needed] information and refer them to the right person.”

“I wanted my patients to view me as a provider of preventive and curative medicine and someone that would listen to them. This started with Touro—they trained us to listen. I think Touro deserves the tip of a hat for being one of the first schools in New York City to have a PA program, and a vibrant one at that; a program that is continuing to this day. I'm just thrilled to be part of any commemoration that celebrates Touro.”