Curing AIDS, One Patient at a Time

Dr. Daniel Berger’s Remarkable Medical Career Began in Touro

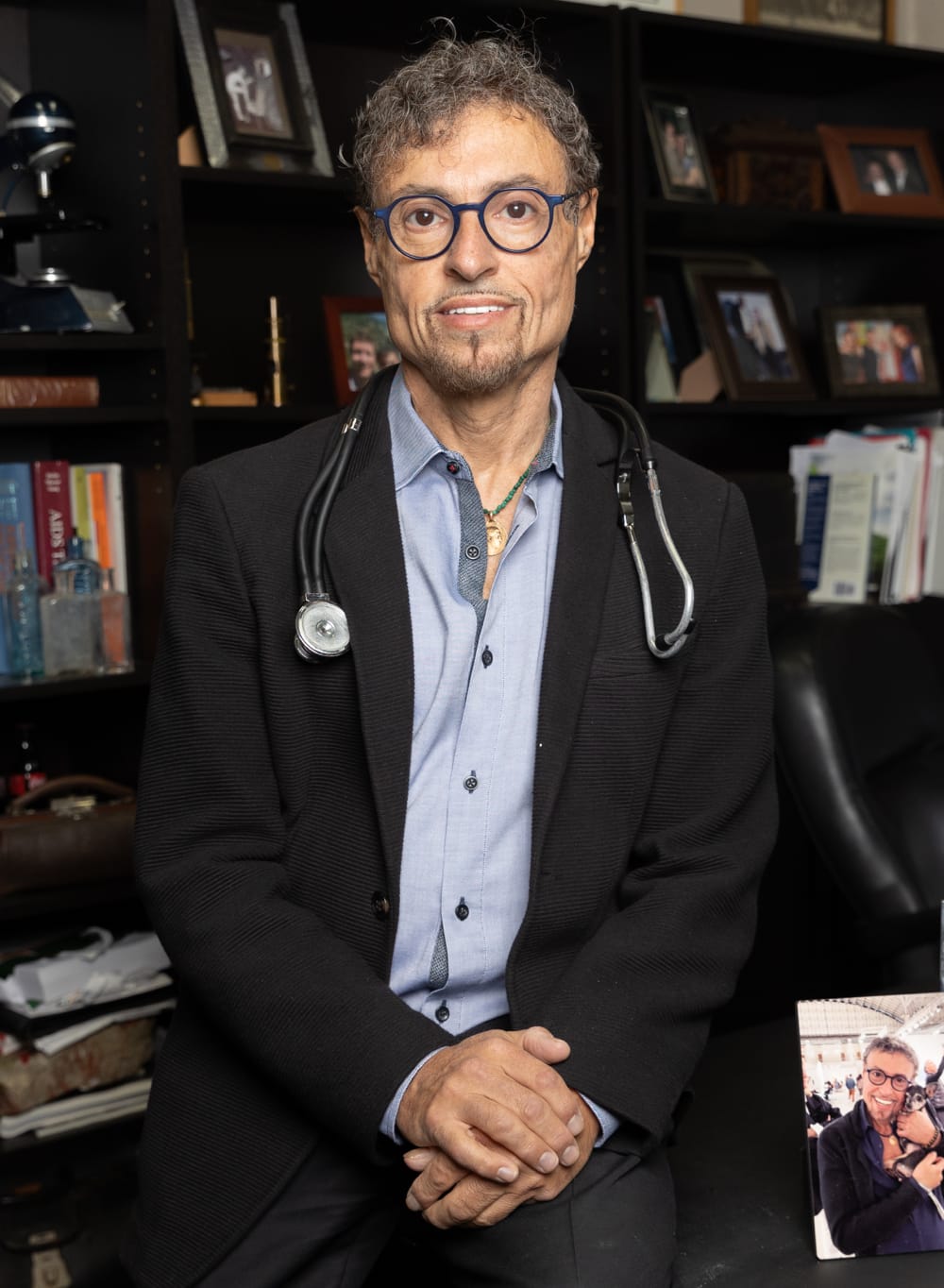

One of the world’s leading HIV/AIDS virus researchers credits Touro with helping him take the first steps in what has become a long and august medical career.

The son of Holocaust survivors, Dr. Daniel Berger attended a leading religious school in Flatbush which was not regarded highly for its secular subjects. “It was an erudite school of learning emphasizing Orthodox texts as opposed to secular subjects,” recalled Dr. Berger on the phone from Chicago where he lives and where his clinic is located. “A small percentage of students went to college, but there was a big emphasis on going to Kollel instead.”

A chance encounter on a train between his father and Dr. Bernard Lander, Touro’s founding president, set Berger’s path. “They struck up a conversation,” said Dr. Berger who enrolled in Touro in 1976. “My father said that I was looking to go to college and Dr. Lander had me come in to talk with him.”

Forty years later, Dr. Berger is still grateful for his experience. “Touro was amazing,” said Dr. Berger. “I loved it. I loved the fact that it was a small school and we received individualized attention. I never found a single teacher who I couldn’t talk to one-on-one or who wouldn’t take the time to help me gain a greater understanding of whatever class it was. I’m thrilled to this day by the education I received at Touro.”

“I was able to succeed because of the way the program was organized, and the way people dedicated themselves to their students,” continued Dr. Berger. “Dr. Lander was a great leader, and his dedication inspired the faculty.”

A Civic-Minded Education

At the time, Touro modeled its liberal arts courses after a popular Ivy League model.

“Literature was paired with history; for example, we matched medieval history with medieval literature,” said Dr. Berger. “The classes and the reading lists were amazing. We read Plato, Greek, and Roman tragedies alongside Greek and Roman history. It opened my eyes to the world. In each class you had to write three papers per class, so I was writing at least six papers a semester. It sharpened my writing skills and provided me with the tools I use today.”

“Unlike other professionals I am able to write a paper in lay and medical terms. That was a skill I developed at Touro.”

Dr. Berger’s close relationships to his teachers enabled him to pursue his interests. He recalled petitioning the school for a class on Latin, which he eventually took with only one other student signing up for it. “Touro didn’t even have a graduating class,” said Dr. Berger. “Touro was a very young institution so I had a very special experience and a very special education that I would not have gotten anywhere else.”

Another positive factor in his experience was the high caliber of teachers. “Our biology teacher taught biology classes at a medical school,” said Dr. Berger. Humanities teachers also pushed the young Berger to explore New York City. “They encouraged us to go to off-Broadway shows and visit landmarks,” he said. “I ate lunch next to the musician Harry Chapin one day.”

Finding His Place and a Community

Before graduating, Touro required each student to complete a senior thesis. Dr. Berger did his thesis on transplant research and spent a year as part of a transplant team in Downstate Medical Center, another experience that would affect his future.

“I watched the first human intestinal transplant and the team studied how to perform liver transplants using animal models,” said Dr. Berger who also gained practical experience from the thesis. “I was suturing up pigs. I was very much involved even though I was a college student; don’t ask me where I found the time.”

After graduating, Dr. Berger attended Chicago Medical School in the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. In med school, he won a student research award from the American Diabetes Association and spent an additional year studying diabetes physiology in rats.

“I always wanted to become a doctor,” explained Dr. Berger. “My family doctor was great, and I really valued his work and identified with it. My father tried to convince me to become a dentist, but I thought becoming a physician was so much more interesting.”

His entrance into the medical field coincided with the devastating HIV/AIDS epidemic that affected the gay community, of which he is a member.

“I pivoted since I had this research background and there was no treatment of HIV/AIDS. I wanted to use my skillset to help others. Every day you heard about someone going into the hospital and watched patients getting sicker and sicker.”

Fighting and Curing AIDS in Chicago

Dr. Berger chose to do his residency at Chicago’s St. Joseph Hospital because it was the first hospital in the city with a dedicated AIDS ward. While many of his colleagues left Chicago after finishing medical school, Dr. Berger opted to stay in the city to continue working with AIDS patients. His work immediately began attracting notice and Dr. Berger eventually launched Northstar Medical Center, a specialized clinic that became the hub of research and treatment options throughout the state.

“What we were doing was unheard of since most places that do research are university hospitals, but we were a private clinic using the latest therapies to help our patients combat something that wasn’t well understood.”

One of Dr. Berger’s signature approaches was to treat patients in his clinic with a range of therapies, not solely focused on curbing the immediate effects of the disease. “A lot of patients were dying from malnutrition, so we brought in nutritionists and developed nutritional intervents that included human growth hormone for AIDS wasting. We worked with many candidate anti-retroviral agents to combat the virus, working with pharmaceutical companies; we brought in psychologists to help our patients deal with depression and mental health issues.”

At its peak, the clinic was the largest private HIV clinic in Greater Chicago and treated 10,000 patients. The clinic employed five physicians and five study coordinators who worked alongside nurses and physician assistants.

“A lot of doctors didn’t feel that any of the drugs were working,” recalled Dr. Berger about the grim mood of the era. “Many patients were told they had six months to live and they came to me to see if I could help them—many of those same patients are still alive today. If you are diagnosed with HIV today, you can have a normal life expectancy.”

Dr. Berger helped pioneer the groundbreaking approach to HIV by treating the disease with several drugs at the same time—a treatment plan that eventually managed to control HIV—an idea Dr. Berger said was inspired by his father’s experience. “My father had tuberculosis after World War 2 and he was sent to a sanitarium,” Dr. Berger explained. “The standard care for tuberculosis treatment were three drugs combined together… HIV/AIDS wasn’t really well understood, and we used sequential monotherapy: if one drug didn’t work we would put our patients on another single drug, but none of it was working. And to continue doing something that isn’t working is insanity.”

In 1992, Berger presented the world’s first study of combination HIV treatment at the International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam. It was the stepping stone to what later became known as the AIDS cocktail. His clinic ran more than 200 clinical trials and Dr. Berger is the author of dozens of scientific papers that have appeared in prestigious medical journals like The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine. Many of the patients who were sent to him during the heyday of the crisis are still alive, he noted.

“My patients were able to survive a deadly disease and live an almost normal life,” he said. “That I was able to contribute to that effort is what I’m most proud of.”

For his work, Dr. Berger has received a dizzying array of accolades. Most recently, he received the Visual Aids Vanguard Award, for his “exceptional work as an HIV specialist who has made essential contributions to HIV and AIDS medical treatments.”

A Bashert Career

Though the AIDS epidemic has long receded, Dr. Berger is as busy as ever. His clinic has continued to run drug trials for drugs to treat HIV and he was an investigator studying the antiviral that treats COVID.

“I had nightmares,” said Dr. Berger. “Many of my patients are immune-compromised due to HIV/AIDS; many of them have diabetes and heart disease and we knew that the risks were higher for them. I worried I would lose patients like in the early days of the AIDS crisis.”

Dr. Berger stayed in close touch with his patients and promoted a plan in the clinic of cocktails of vitamins and social distancing to deal with the risks of COVID. Though some of his patients were hospitalized during the epidemic, “I didn’t lose anyone,” said Dr. Berger.

Dr. Berger credited his success to his tenacity and an old-fashioned stubborn unwillingness to give up.

“It’s a family trait,” he concluded. “My parents were Holocaust survivors. They were stubborn and I share that stubbornness in my dedication to research and my feelings about the importance of research.”

“I think on a broad level we wonder what our purpose is in life and how to make a difference. My parents survived the Holocaust for a particular reason; I don’t think it’s a coincidence that I’m their son and it’s also not a coincidence that I developed as a physician during the AIDS epidemic, which was another holocaust. I think there’s a reason why I’m here.”